Mother-daughter relationships: Leonora Christina Skov and Yang Mingming

Mother-daughter relationships: Leonora Christina Skov and Yang Mingming

Mothers and daughters form a speciel bond, sometimes through love, sometimes through pain. As the Chinese saying goes: 相爱相杀, the relation is often double edged. In the presence of the nearest and dearest, we can hurt each other, deliberately or unintentionally, but in our hearts there is still a lot of tenderness.

Reflection of Each Other. Talk in Danish Cultural Center in Beijing

Together with the Royal Danish Embassy in Beijing, Danish Cultural Center is organising an in-deep talk with Danish author Leonora Christina Skov and Chinese film director Yang Mingming. Both daughters have recently dealt with the mother relation in their new, highly claimed works and will share their personal experiences on the topic.

When: Thursday 16 May at 19.00 in Danish Cultural Center in 798 Art District Beijing

Speakers: Leonora Christina Skov and Yang Mingming

Moderator: Li Wenjie

Free Entrance

The talk is part of Danish Cultural Center’s focus on gender and equality in 2019. It is dedicated to mothers and daughters who are hovering on the edge of love and hate, denial and acceptance.

The quiet sense of something lost

Two years ago my mother died after a twelve-year struggle with breast cancer. Our relationship wasn’t close, although I did everything I could to get closer to her during her last few years. It was the influence of death, I thought, but no matter what, I never felt that I knew her, or that she liked me much.

Immediately after her death I decided to write an autobiographical book about our difficult relationship. I’m an only child in a family that on the surface looked ordinary, but underneath was governed by my father’s countless inscrutable rules and my mother’s all-persvasive fear of other people. At the age of nineteen I moved to Copenhagen to study literature at the university, and the following year I began a relationship with a female priest, and came out to my parents. My parents reacted by burning all my things. I didn’t see my parents for many years. My mother regularly threatened to die, and when she got cancer she blamed me. If my mother died of grief, I was afraid it would be my fault.

After my mother’s death I expected the story would write itself. I didn’t have to invent characters, voices, spaces or scenes, but one year later I hadn’t written a line. Instead I’d seen my mother’s accusatory gaze before me every time I sat down at the keyboard. My wife, Annette, pointed out that at the end of all my novels a letter appears that sheds light on all the terrible secrets people have been carrying around and reveals what really happened. I was probably hoping to find a similar explanation this time, but all my mother left was some jewellery and my unopened presents.

I’ve spent years of my life trying to interpret her words and actions, but she’s still a mystery to me, so I decided early on to lay it all out for the reader without interpreting it. For me the story is vitaly important. I feel a deep sense of astonishment about what happened to me, and profound gratitude that I was able to survive and write about it all.

About Leonora Christina Skov

Leonora Christina Skov lives in Copenhagen and has published six novels and two children’s books. She is a literary critic with weekly Danish newspaper Weekendavisen, holds and M.Sc. in comparative literature, and is the recipient of The Danish Arts Council’s prestigious three-year grant. As an avid traveller, she has been a writer-in-residence at Ledig House/ Writers Omi in the US, Sangam House and Chennai Mathematical Institute in India, Swatch Art Peace Hotel in Shanghai, Château de Lavigny in Switzerland, Hawthornden Castle in Scotland, and the Danish institutes in Greece, Paris, Damascus, and Saint Petersburg. In 2016, she participated in The Kala Ghoda Arts Festival in India, and Dhaka Literary Festival in Bangladesh.

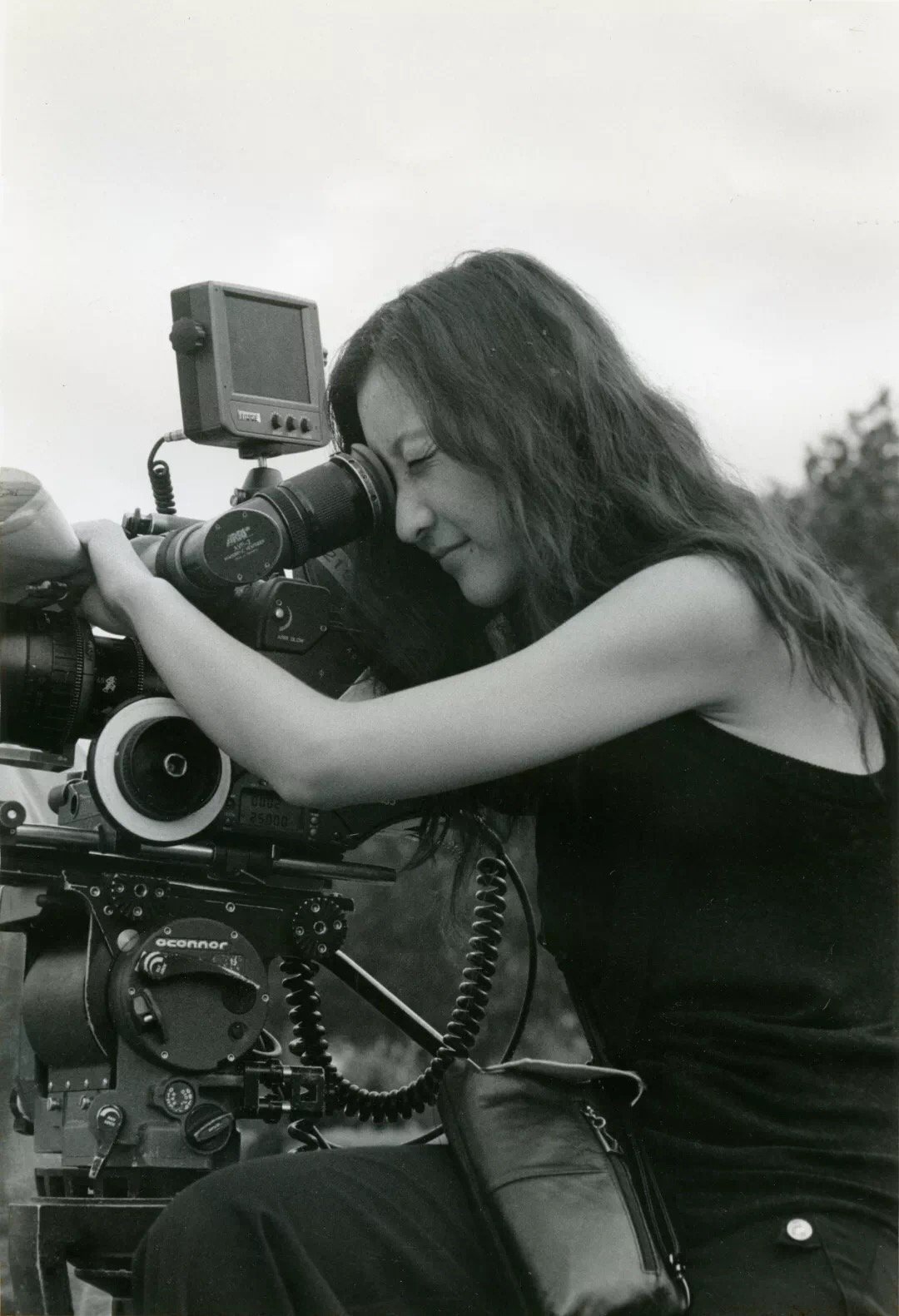

Girls Always Happy

Yang grew up with her own mother in the same area. The film is not only imitating the intensity of a family relationship, but also depicting the condition of a Hutong shared home and it´s every nook and cranny, as well as the environment of their neighbourhood. Affection also resonates in these fluid shots of everyday locales, reflecting the realization at the film’s core: what we love and what we struggle with are often the same thing.

About Yang Mingming

Yang Mingming was born in 1987 and graduated from National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts. She directed, photographed, and starred in her short debut Female Directors, which marked the new creativity of young directors. It was one of the top ten Chinese independent films in 2012, and showcased in youth film festivals both home and aboard. In 2015, she edited Yang Chao’s feature film Crosscurrent, which won the Silver Bear for Outstanding Artistic Contribution. Girls Always Happy is the first artistic feature written, directed and performed by Yang Mingming. Girls Always Happy is selected in the Panorama of 68th Berlin Film Festival.The film will be released on May 17, 2019 on the Nationwide Alliance Of Arthouse Cinemas.

Moderator Dr. Wenjie Li is an associate professor affiliated with School of Foreign Languages and Literatures, Beijing Normal University. She has received her PhD degree from Copenhagen University and was awarded “H. C. Andersen Prisen” in 2017 for her research on the Chinese translations and interpretations of H. C. Andersen’s tales. Her major academic interests include translation studies, comparative literature studies, and intercultural studies.

For further information, please contact Danish Cultural Center in Beijing: center@danishculture.cn