Everything is connected – interview with author Grzegorz Wroblewski

Interview with author and artist Grzegorz Wroblewski

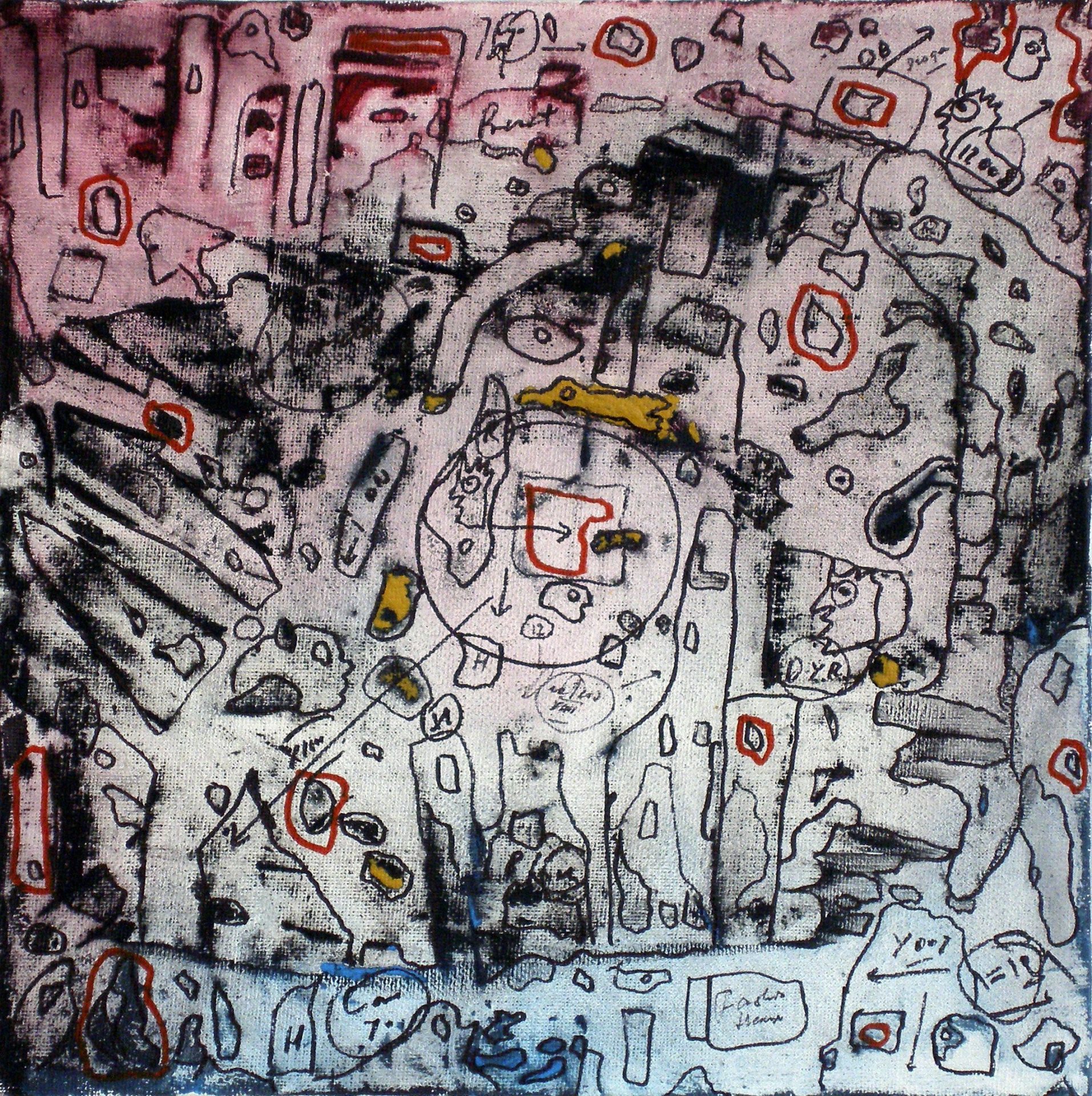

Polish born author (and much more) Grzegorz Wroblewski lives and works in Denmark and has collaborated with Danish Cultural Institute on several occasions. His works are characterized by a kind of meditative mode, making it possible for different threads of meaning to intertwine between each other, increasing the impact on the reader while the precise meanings of individual elements are kept slightly out of touch. The texts have great energy and a wry humor that pokes fun at society and the reader herself, but not without an ironic concept of self.

Last year Wroblewski presented his experimental essay collection Miejsca Styku at DCI in Poland and took part in the literary festival Puls Literatury in Łódź. We met him for a talk about literature, national identity and the connectedness of all things.

Interviewing Grzegorz Wroblewski is not necessarily easy, but in return it is very rewarding. He has a way of answering questions in a way you did not expect, but which broadens the horizon of the conversation.

In other words, Wroblewski does not give easy answers to by-the-numbers questions, and when he describes the world, he strays away from all-too-well-established categories. He is a detective, using a kind of artistic-scientific approach to investigate what it means to be human and live on planet earth. With a bit of a cliché, you could say that he wants to raise questions rather than provide answers. And he is fundamentally intrigued by the ways in which everything is connected, in the world in general as well as in the worlds of art and literature.

When I ask him what genre Miejsca Styku belongs too, I do not get a straight-forward answer either:

It is a kind of essay collection, but it is a hybrid, really. I have created a special concept, bringing together interviews with me, examples of my poetry, plus articles about culture and political subjects and about all my experience in different kinds of media that I have worked with. I have written prose, drama and poetry, but I have also worked as a visual artist. And in my long life, I have met many people in Denmark, Poland and the USA. Miejsca Styku is about all these things, actually.

Grzegorz found DCI in Warsaw to be a fitting place to discuss the book, all the more because the subject matter is, among other things, the meeting of minds between creative people.

The cultural institute was a very interesting place to present Miejsca Styku. We talked about many different nuances of the ways in which artists can connect, how they can collaborate and so on. So, it was a good platform, many people attended, and I think it went well.

I have been there with several Danish authors, over the years, e.g. Louise Rosengreen, because her poems had been translated into Polish, in several Polish cultural magazines. So, we preapared a presentation in cooperation with Bogusława (Bogusława Sochańska, director of DCI in Poland, ed.).

Copenhagen is not Scandinavia

One of the subjects I would like to hear Grzegorz Wroblewski weigh in on, is how he perceives the Danish national character. So-called Danishness has been the topic of much debate in the political and cultural public sphere. I figure he must have a unique vantage point regarding “seeing” what is truly Danish; originally from Poland, living in DK since 1985, and very much international in his outlook. But even though he mentions some characteristics that could be considered Danish, e.g. cross-generational cooperation, he quickly opens different dimensions of the question.

The world is constantly changing. I do not think the things I experienced in Denmark in the late 80’s or in the 90’s exists anymore. New generations arrive, and of course they learn about history, they know of the Danish past, they know Danish culture, all the things they have inherited from their parents and grandparents. But in the world of today it is difficult to get a hold of a kind of specific Danishness.

To give you an example, Copenhagen is kind of special. When people in Poland ask me: you live in Denmark, what do you think of Scandinavia? Then I have to answer that I do not know much about Scandinavia, because I live in Copenhagen. To experience a more classical version of Scandinavia or Denmark, maybe we need to go to Jutland. To me Jutland is more like Sweden than Copenhagen is. Copenhagen is a transit city, between Scandinavia and Europe. But still, it is the Danish capital, so you would expect some Danish signals to be present…

In this way, the thoughts flow from the author, giving a clear impression that he thinks while talking. It is equally clear, though, that he is carefully considering the answer to any question he is posed. In regard to establishing what is truly Danish, Wroblewski seems to suggest that some things do characterize our small country after all, but in an instant, he undermines his own argument and draws attention to the global picture.

We can observe each other, of course, and we can come to certain conclusions. How do we differ? How do we talk, how is the language constructed, what are our traditions like, what is our food culture, how do we eat, how do we treat each other, what kind of music do we play, what is our visual art like?

If you take Danish architecture and compares with Polish architecture, the Polish tradition is more bombastic, with many ornaments and effects. In Denmark, less is more. You can talk about a special brand of Danish modernism, the experiments of Arne Jakobsen, the development of collectivistic dreams which turned sour in Poland because of the historical circumstances.

But your question is an open inquiry for me. I keep pondering: what is Danish in relation to the planet? We forget that we all live on the same planet, and then we think we are from Amager, Nørrebro (parts of Copenhagen, ed.), Warsaw or New York. But if we are from New York, are we then from Queens or Brooklyn? You can keep going in this fashion. I think along these lines a lot, and I can give you billions of examples of something typically Danish. But then, if I think more profoundly about it, I can not put my finger on anything super special, which is drastically different from other countries. At the end of the day we are Homo Sapiens.

Poetry as science

It is the constant investigation of these Homo Sapiens, and all the peculiar cultural subdivisions we create, such as nationality, that is interesting for Grzegorz Wroblewski, and which his work centers around. When I make the comment that there seem to be something scientific about his texts, it quickly becomes apparent that this is a connection that others have drawn before me.

There is a Polish literary critic, Anna Kałuża from the University in Katowice who has worked with my books and activities. She is of the opinion that my literary production ought to be considered as a kind of anthropological or ethnographical research. When I wrote my notes on Copenhagen (”Kopenhaga”, ed.), which was also published in the USA, many people asked me questions along those lines, when I promoted the book in Boston.

I work quite similarly to Levi-Strauss (famous Belgian anthropologist and ethnologist, ed.) in ”Kopenhaga”, I try to observe all the rituals people perform in Copenhagen. How people talk to each other, how the weather influences our small dialogues, our little rituals at home and so on. It was a kind of experiment: what is the relationship between the people in Copenhagen and is it possible to have a dialogue between the rituals of Copenhagen and the dealings of people in more “exotic” places?

In the middle of his existential considerations, Grzegorz unexpectedly arrives at a specific phenomenon, connected to the Danish capital, and even to Danishness itself.

I have worked with many musicians in Copenhagen, among other things, they have accompanied me while I read from my poetry. They were people from the scene for improvised jazz. When I talk to these people, they tell me that even though musicians in Berlin or Paris play the same instruments, Copenhagen is a kind of Mecca for contemporary, improvised jazz. I have experienced the same thing, I have never encountered as many new, young jazz musicians as in Copenhagen. That too, is Danishness to me.

Improvised jazz as part of the Danish spirit may be a surprising idea for many people, but it is a suggestion that points to the possibility of looking for those characteristics of a country that would not be included in the tourists’ guide.

The personal and political world

Just as seamlessly as Wroblewski switches between the local and the global in conversation, he moves naturally between personal observations and social and political commentary in his writing.

It is unavoidable that art, politics, economy, personal concerns and so on are linked tightly to each other. Art and poetry must react to the dealings of the people around us, but you have different methods with which to react. If you write existential poems they can reflect your emotions as well, and that is also a reaction to the world surrounding you. So politically active poetry does not necessarily have to be very concrete.

You can write about everyday life, you can go shopping for groceries and write a small report that becomes a very strong political statement. Even if you create ornament, make a cryptic book and write very secretively you can smuggle many interesting things through the text. Talking about politics, I have never become completely sure about what political means. Is it supposed to be a poster, or should it be secret, dreamlike?

It is apparent that if you follow Wroblewski’s line of thought everything is connected; the deeply personal can be political and any political decision has personal consequences.

It is not simple, this tension; individual experiences and the civil society and the ecological side, plus the system, tradition, religion, economic aspects and so on. Often the tension leads to conflict, but that is not necessarily negative. Sometimes this is a positive situation.

Wroblewski explains how culture moves forward through the tensions between the conservative and the experimental.

For example, we all know about the success of Danish and Swedish crime stories, they are known throughout the world. My personal theory though, is that exactly this kind of popular culture and literature (produced in DK, ed.) has had so much success because of the good political decisions of the Danish Arts Foundation. It supports many different artists and authors and some of those authors experiments a bit more with different kinds of literature, which in turn provides a lot of tools and ideas for the authors of popular literature. So, the ones doing the experimenting are not isolated, it is an organism. If I had to be brutal I would call it a kind of investment; you invest and support the experiment, but the experiment provides opportunities for the creators making money, e.g. the authors of crime stories. The Danish crime novelists are extremely good technically, because they have the proper tools at hand. That is my theory.

The poet also reflects on the role of his own production in the common human consciousness.

My literature is pessimistic, existential and pessimistic. But this is not because I wanted to spew my pessimism out on other people, quite to the contrary, actually. It is because I think that existential consciousness can make people stronger, maybe they will understand things differently and be able to think a bit more – what to call it? – panoramically, in their daily lives.

Networks are more important than statues

When it comes to naming authors from his country of origin which have inspired him, Grzegorz Wroblewski is himself quite panoramic in his overlook on literature.

Sometimes you should think statistically. Poland is a rather large country, consisting of about 38 million Poles, plus you have an extensive diaspora of around 10 million that has a connection to Poland. That is quite a big number of people who understand and are able to write in Polish, so statistically the language is sizeable in the world of literature. The same goes for the USA, for example.

Coming back to Poland, we have many interesting authors. One example is Andrzej Bursa. He has only written 35 poems, he was sick and died young, so there was no possibility to continue the authorship, but those 35 poems have influenced me a lot. It was a kind of mix between objectivistic and existentialistic literature.

We have different literary traditions in Poland, just as in Denmark. You can find interesting authors working with economical literature, feminist literature, cyberpunk and so on. Absolutely like in Denmark. Then you follow your own aesthetic sensibility and decide which authors are good.

It is not surprising that the deciding characteristics of Wroblewski’s influences have had more to do with stylistic expression than national borders.

People in Poland has kept asking me, where I have my traditions and my role models from, which authors have been the most interesting for me. I have always had an interest in objectivistic literature, e.g. Charles Reznikoff or Williams Carlos Williams (both from the USA, ed.). There are some strings connecting me to meditative sides of people. This affinity in interplay with the intense European tradition can produce intriguing results.

The main idea remains clear, Grzegorz Wroblewski finds networks of influences, always moving, more interesting than canonical artists or works. When he speaks on distinguished Danish names like H. C. Andersen or Søren Kierkegaard, he stresses that contemporaries in their time created literary products similar to theirs. Michael Strunge (a very well-known poet in Denmark) was influenced by the British punk movement, and his works reached a higher plateau than they otherwise would have, by their interrelatedness with the productions of other important Danish contemporaries. In the world of film, Wroblewski describes how Lars von Trier and the other “dogme” directors built on the ideas of Polish directors Kieslowski and Majewski, both of which taught in Denmark for a while.

All the observations of connections Wroblewski has made through his life are poured into his work. This great amount of knowledge and considerations gives his writing great weight, but at the same time, the will to smile lives between the lines.

Grzegorz Wroblewski has written poetry, drama, essays and more, collaborated on several projects with artists and musicians, and works with visual art. He has contributed to Danish and international magazines and journals.

Besides being translated into Danish (Wroblewski writes in his mother-tongue) versions of his work has been published in several countries, the list of publications include: Pjesme (Bosnia-Hercegovina, 2002), Our Flying Objects (England, 2007), A Marzipan Factory (Australia, 2010), Kopenhaga (USA, 2013), Let’s Go Back to the Mainland (USA, 2014), Zero Visibility (USA, 2017), Hansenovic vana (Czech Republic, 2018).

In December 2019, Grzegorz Wroblewski will collaborate with DCI once again, presenting a visual project based on his book Nowa Kolonia (The New Colony). The exhibition will take place at Muzeum Literatury in Warsaw and is a cooperative project with artist Doris Bloom.

Text: Adam Kalkrup